Now, it is officially available to the public.

The film is about finding out a Black girl’s name who two strangers found decapitated on Feb. 28, 1983 in an unabandoned building located at 5635 Clemens Avenue in the city’s West End neighborhood. It was a part of a larger community originally called Cabanne.

In the film, Joseph Burgoon, a former detective who worked on the case until his retirement, said the strangers were rummaging for scraps after their car broke down. One of the men flickered their lighter and saw her body laying in a corner of the basement.

Burgoon said the unnamed men ran outside and immediately called police to report the incident.

He also said he and other officers initially thought she was an adult prostitute or a drug addict because she was laying face down nude, but when they turned her over, they realized she was a child.

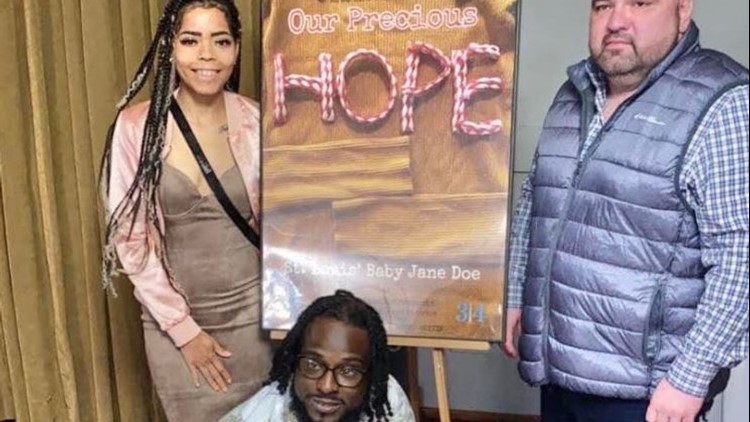

Eric McAlister, who lived two blocks over from the crime scene, said at the screening he wanted to give his perspective as a ten-year-old boy.

He said he was at the crime scene and witnessed commotion from adults who were concerned about the tragedy.

“My friends and I came from the park, and all the kids gathered around to see over the crowd,” he said. “We climbed this tree that was about 12 feet high for a visual over top of the crowd to see what was going on, and we heard it was a deceased body. We didn’t know the details. Then, as minutes went by with talk from the crowd, it was revealed it was a child.”

The question was asked if the situation had a major effect on his childhood at the screening, and he said it not only affected him, but it impacted the community.

He said families weren’t allowed to visit and spend the night at each other’s house anymore. He added schools were stricter about attendance by doing headcounts every day and accounting for every child in their classroom.

Burgoon said he and other officers contacted schools in town about missing children, but they ran into some challenges. It was later determined kids were unable to be tracked after transferring schools due to schools terminating secretaries because of a budget crisis. Police notified families, but they never received word back from any parents.

The search continued, and the FBI, NCIC, NAMUS, VICAP, the Missing Persons Unit, and other organizations were contacted with the hope of potentially receiving leads and more information about who the girl is. The case even received national attention. Burgoon appeared on an episode of “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” with other detectives around the country to discuss the case.

Burgoon said Captain Leroy Adkins, the first African American to head the city’s homicide division, delayed Hope’s burial for nine months, assuming her family could come forward with information, but it never happened. She was finally laid to rest Dec. 2, 1983, at Washington Park Cemetery.

In May 1984, a group of high schoolers from Livingston, Illinois, raised money to buy a headstone for her grave.

In 2009, detectives went to the cemetery to find her grave to start the exhumation process, but instead, they left in a disarray. Three bodies were crowded together, and none of them were hers. Her headstone was also placed on the wrong grave.

The medical examiner’s office declined to authorize another dig unless the exact location of her grave could be verified. Researchers were eventually able to locate her body, thanks to a photo captured by a Belleville photographer.

A second digging took place in 2013, and she was found. Detectives were able to find her grave and determine it was her based on the decapitation at her shoulder level.

Freddie Jefferson, an exhumation volunteer and veteran, helped find her the second time.

“We were hoping [the] water didn’t sink in because it stormed that day,” he said. “We worked very hard to get the casket open. We finally got it open, took her body bag out, and hauled it out.”

She was taken to the morgue where samples were extracted and sent to the Smithsonian Institution. Mineral tests determined she wasn’t originally from St. Louis.

Burgoon said the medical examiner’s office, the morgue, and a forensic anthropologist determined she was between the ages of 8-11, 61 pounds, the height of 4’10” without her head, and between 5’3”-5’4” if the head were still intact.

A one-hour reburial was held Feb. 8, 2014, at Calvary Cemetery’s “Garden of Innocents,” an area designated for unidentified individuals.

The St. Louis Police Department dedicated a room to “St. Louis Baby Jane Doe” and are still actively working on the case.

“We’d like to find out who she is, who did that to her and get with the family to let them know we never forgot her,” Burgoon said. “We did the best we could.”

Sosa said his motivation for making the film comes from remembering his late mother telling him as a kid to come inside because little kids’ heads were being cut off.

“When you’re seven, eight years old, you don’t know what she’s talking about, but it always stayed with me,” he said. “My mom and I talked a lot about this case, so I dedicated the film to her.”

Lee Barber, assistant director of the film, said what sets their documentary apart from information that’s already out there are interviews from Burgoon, McAlister, and Jefferson and having the coroner’s report.

“That's the reason why we wanna get it out there because the new information that we are able to bring to the public will hopefully generate new information on finding who she is ‘cause that’s the main thing,’” he said. “That’s the biggest reason why we did the documentary, so she can be laid to rest under her own name and not as a Jane Doe or a Precious Hope. She’s very precious, but we want her to be buried under her own name.”

If anyone has any information or tips about the St. Louis Jane Doe, they can call 1-866--371-TIPS(8477) or email homocidecoldcases@stlpd.org.

Precious Hope: St. Louis’ Baby Jane Doe is available to watch now on http://314birdstudios.com/, Roku, YouTube, and Amazon Fire TV.