HONOLULU — The message from Hawaiian and FEMA authorities has been consistent: Shelter at home and ride out Hurricane Lane.

But, what about people who can’t?

With Lane already battering the Big Island on Thursday, the warning by Hawaii Emergency Management Agency Administrator Tom Travis that the Aloha State does not have enough shelter space set off alarm bells in an area not used to dealing with such huge storms.

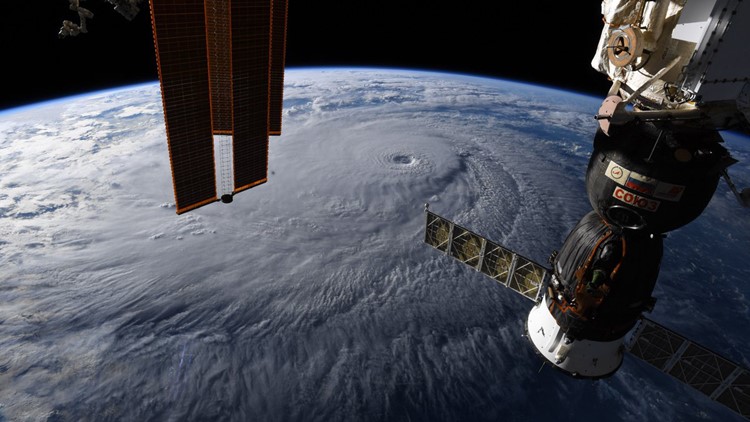

Only three hurricanes have made landfall in Hawaii since 1950. Lane’s projected route may keep it just off the islands, but its powerful winds, voluminous amount of rain – up to 30 inches in some areas – and the accompanying high surf and swell are already creating major trouble.

Gov. David Ige also pitched in with a Wednesday tweet that said, “Shelters are intended to be a last resort option for residents and visitors without safer options to use at their own risk.’’

On Thursday afternoon, though, conditions on the ground did not call for concern about running out of space to find safe harbor.

On the Big Island, which saw some 1,700 residents evacuated three months ago because of the Kilauea volcano eruption, there was room at five shelters for about 7,000, and only about 20 had checked in, according to Maurice Messina, deputy director of parks and recreation.

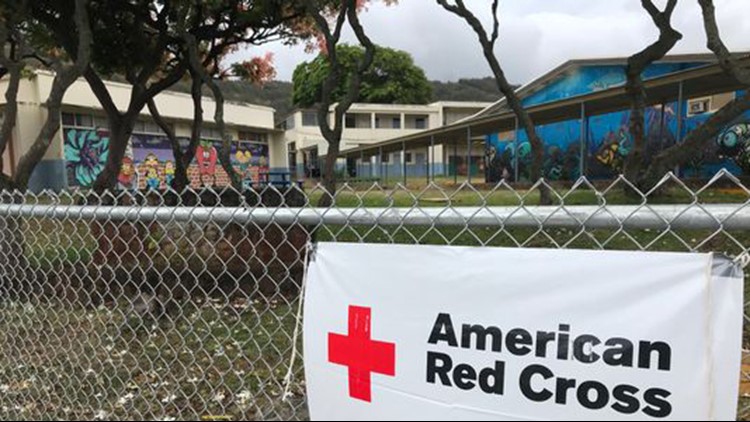

At Honolulu’s Dole Middle School on the island of Oahu, about 10 folks had sought shelter at a hastily assembled evacuation center by mid-afternoon.

Andrew Pereira, communications director for Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell, said the city and county expects to be able to house all who need it.

A state report released in February indicated Oahu had 182,797 shelter spaces, or about one for every five persons on an island with a population of just under 1 million. The Big Island, with a population of 198,000 and 36,539 spaces, has a similar ratio.

PHOTOS: Hurricane Lane approaches Hawaii

“I think you’ll find that in any hurricane-ready community, you don’t ever have enough shelter space for the entire population,’’ Pereira said. “The standard operating procedure in most communities that can be impacted by a hurricane is to shelter in place, and that’s what we’re advising our folks to do.’’

That makes even more sense in Oahu because, as Pereira acknowledged, some of the schools that typically double as shelters are not rated beyond tropical-force winds, and even a weakening Lane was producing sustained winds of up to 125 mph.

They still provide more protection than the wooden houses with tin roofs that are common in tropical climates, and certainly much more than what homeless people get out in the elements. Pereira said Honolulu had opened 20 facilities by 10 a.m. local time and was providing free bus service for homeless people to reach them.

Most people are encouraged to bring their own bedding, plus food, water and medicines for 3-5 days.

“Those evacuation centers are intended for short stays,’’ said Brad Kieserman, vice president of disaster operations for the American Red Cross. “Their purpose is to allow people to ride out the storm, and after the storm passes, the folks who can go home do, and the folks who can’t are transitioned into emergency shelters, also run by the counties in Hawaii.’’

The site at the Dole school has room for at least 200, said coordinator Jennifer Dutton, who works for the Red Cross out of Los Angeles. She arrived in Hawaii on Wednesday night to begin preparations.

“I’m not sure when folks will begin to arrive. I think everyone is just waiting to see how bad the storm is,’’ Dutton said. “We’ve got some supplies here, but it’s of course limited because we’re on the island. If we need more, we’ll have them shipped in.’’

The National Weather Service says Hurricane Lane in Hawaii has been downgraded to a Category 3 storm, but officials are warning to remain cautious. (Aug. 23) AP

Messina said the facility set up at Pahoa Regional Park as a lava-evacuation area after the Kilauea eruption housed 600 evacuees – 55 of whom remain – and had room for 2,000.

If anybody runs out of space for those escaping harm from the storm, Messina said it won’t be the island of Hawaii.

“On the Big Island, we have more beach and park facilities than any other island,’’ he said, “so if you couple that with our all of our schools, we should be OK.’’

But folks who live surrounded by water realize they encounter different dynamics when a hurricane approaches than those in the mainland. That was part of the challenge for FEMA when assisting victims in Puerto Rico last year.

At a news conference Thursday, agency officials said they would apply lessons in Hawaii learned from the 2017 hurricanes – including Maria, which devastated Puerto Rico in September.

FEMA Administrator Brock Long said there’s already a plentiful supply of generators at hand to restore power if the grid is affected. And Pereira said the agency has set up barges full of supplies ready to be distributed.

But Pereira also noted that Hawaii imports 98 percent of its goods by sea, so any damage to its ports could present serious problems. And, of course, the locals can’t just drive a few hundred miles away to escape danger.

“We are the most isolated land mass on the planet,’’ Pereira said. “You can’t just drive to a safer area like when hurricanes threaten the East Coast, where you see folks driving north or south or west to get away from the storm. We don’t have that option.’’