ST. LOUIS — On Wednesday afternoon, the most up-to-date number of COVID-19 deaths across the State of Missouri was 526.

Of those 526 deaths, 450 of them occurred in the counties that are part of the 5 On Your Side viewing area.

The City of St. Louis and St. Louis County account for 369 of those, which is more than 70% of the total deaths in the state.

The first few recorded deaths in the city were black patients.

Dr. Laurie Punch, who has been working in the COVID-19 ICU at Christian Hospital in north St. Louis County, said that didn't surprise her at all.

"I have not been as mystified by the disproportionate experience of COVID-19 in the black community in the country, the state and the city," Dr. Punch said.

Dr. Punch spoke to 5 On Your Side about the racial disparities in COVID-19 patients weeks before enough numbers were available to find a trend simply based on the patients that she saw in her hospital.

Now that more numbers have been gathered and distributed, data proves what she saw initially has become the current reality.

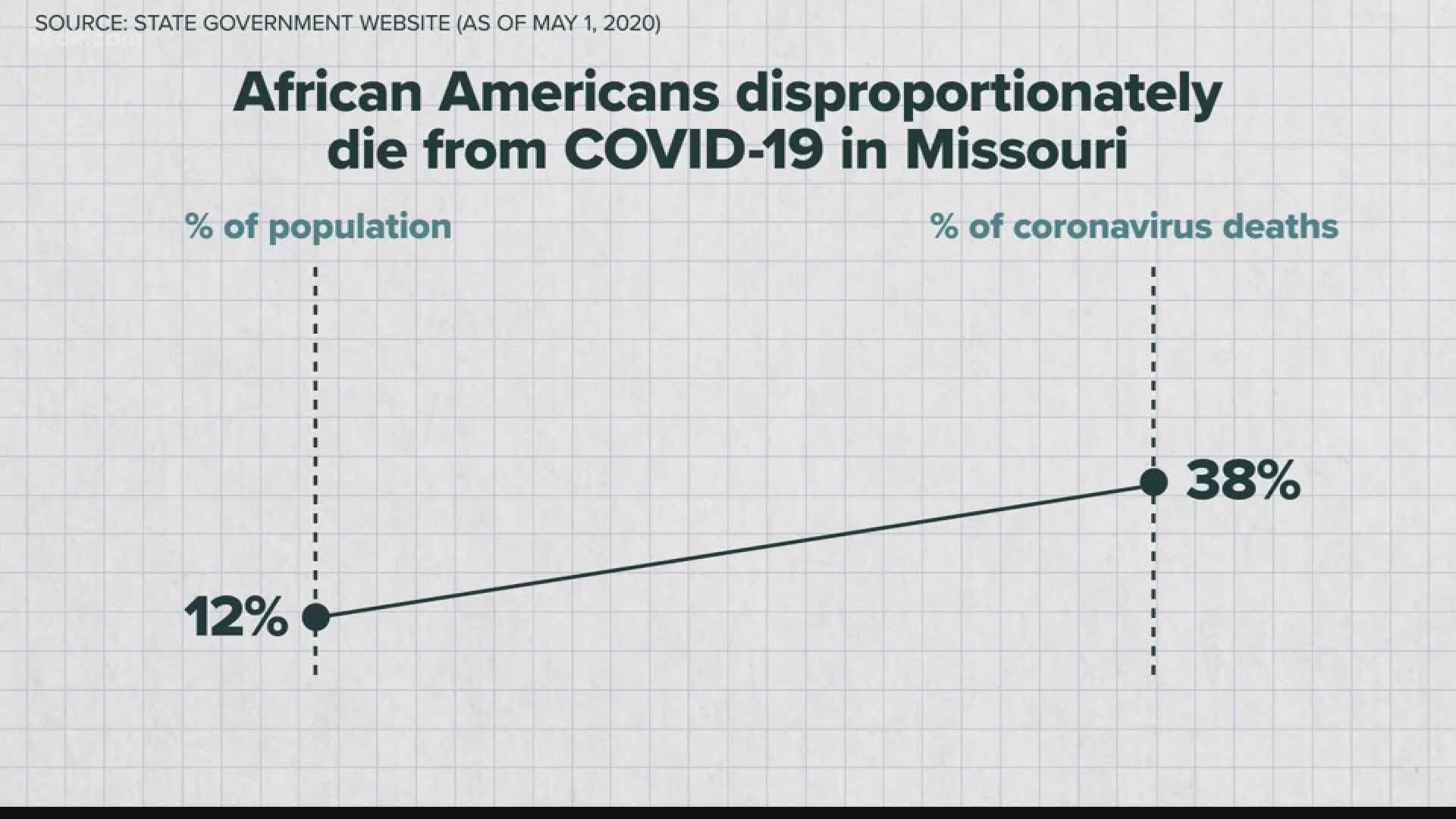

Thirty-eight percent of the people in Missouri who have died from COVID-19 are African American, but African Americans only make up 12% of Missouri's population.

In Illinois, African Americans make up just 15% of the state's population but 33% of the COVID-19 deaths.

Michael McMillan, the president and CEO of the Urban League of Metropolitan St. Louis, said there are a number of social and economic factors contributing to these staggering statistics.

"When you look at essential workers that do not have the ability to work from home, many of them are African Americans," McMillan said. "When you look at individuals who have low-income jobs and have to take public transportation, they do not have the opportunity to shelter-in-place in environments where they can distance themselves from family members."

Data from the United States Department of Labor shows that the number of black and Hispanic people who have the ability to work from home is lower than the number of white and Asian people who can work from home.

McMillan said the disproportionate number of black essential workers coupled with the layout of housing in many predominately black communities makes it very difficult for the people impacted by these factors to social distance and keeps them more exposed to the virus at work and at home.

"We have seen that from a number of different households that have reached out to us for assistance," McMillan said. "Unfortunately, some of those individuals have died the past two months because of what has taken place in terms of the inability to socially distance."

Even with the health risk associated with essential workers, McMillan said the biggest need his organization has been working to meet centers around people who are out of work all together.

"African Americans already have such a high percentage of the unemployment rate compared to the general public," McMillan said. "Especially young African American males 18 to 24."

McMillan said the services they supply year-round have to be ramped up to meet the need created by hundreds of people who are without work because of COVID-19.

"It has reduced people to their basic needs," McMillan said. "Food, clothing, shelter, utilities, diapers, formula. People are just trying to survive. Just two months ago, these people had jobs, were working and had benefits and security. Now, they have lost all that, and they are living in a state of hopelessness and economic and food insecurities so we decided to pivot."

The Urban League has partnered with organizations in the area to host a number of drive-up mass food and supplies giveaways, instead of the usual pantries they make available for people to come to.

Services like this, specifically positioned and tailored to the communities that need them the most are what Dr. Punch said it will take to close the gap that exists for the black community.

"We must asymmetrically approach that, but we haven't done the work to be nimble enough about racism to be able to say 'No, we're going to take racism out of the equation and we''re going to adamantly attack risk'," Dr. Punch said.

Dr. Punch said trying to apply an equal amount of support and resources to every community fighting COVID-19 won't fix the problem because the black community entered the fight at an even greater disadvantage socially, economically, geographically and health-wise.

She said it's important to remember that the black communities in St. Louis city and county were dealing with a different pandemic before COVID-19 came into the picture.

Gun violence.

"We know a lot about how violence spreads from what we know about infectious diseases," Dr. Punch said. "The reverse is also true - 95%, on average, of the folks who die from homicide and suicide in St. Louis are black. So, are we surprised that, in the beginning, every single death in St. Louis city was black folks?"

Dr. Punch said the symptoms may be different, but the outcome and contributing factors are the same.

"Our composure, as human beings, from the time we come out of the womb, is where we live, work, play and learn," Dr. Punch said. "The truth is, in this country, in the state and in the city, that experience is fundamentally different from black folks."

From a medical standpoint, Dr. Punch said an underlying and layered history of poor medical care and resources in black communities and for black patients has contributed to a disproportionate rate of conditions like diabetes, heart disease and hypertension in black people. All of these underlying conditions create potential complications for COVID-19 patients.

"Racism is an independent risk factor for poor health outcomes and black folks. Period," Dr. Punch said.

However, Dr. Punch said it is important note the efforts being made in and around the black community to close the gap.

For example, Dr. Punch is a trauma surgeon who typically works at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. She said BJC and Washington University allowed her to transfer to Christian Hospital to work as an ICU doctor.

"That is the kind of response that we need to see over and over and over again," Dr. Punch said. I am very proud of BJC and Wash U for supporting me and to be able to be at Christian Hospital. That's where the pandemic hit the hardest at first, and that team there is doing incredible work. I'm proud to be a part of that team."

OTHER STORIES