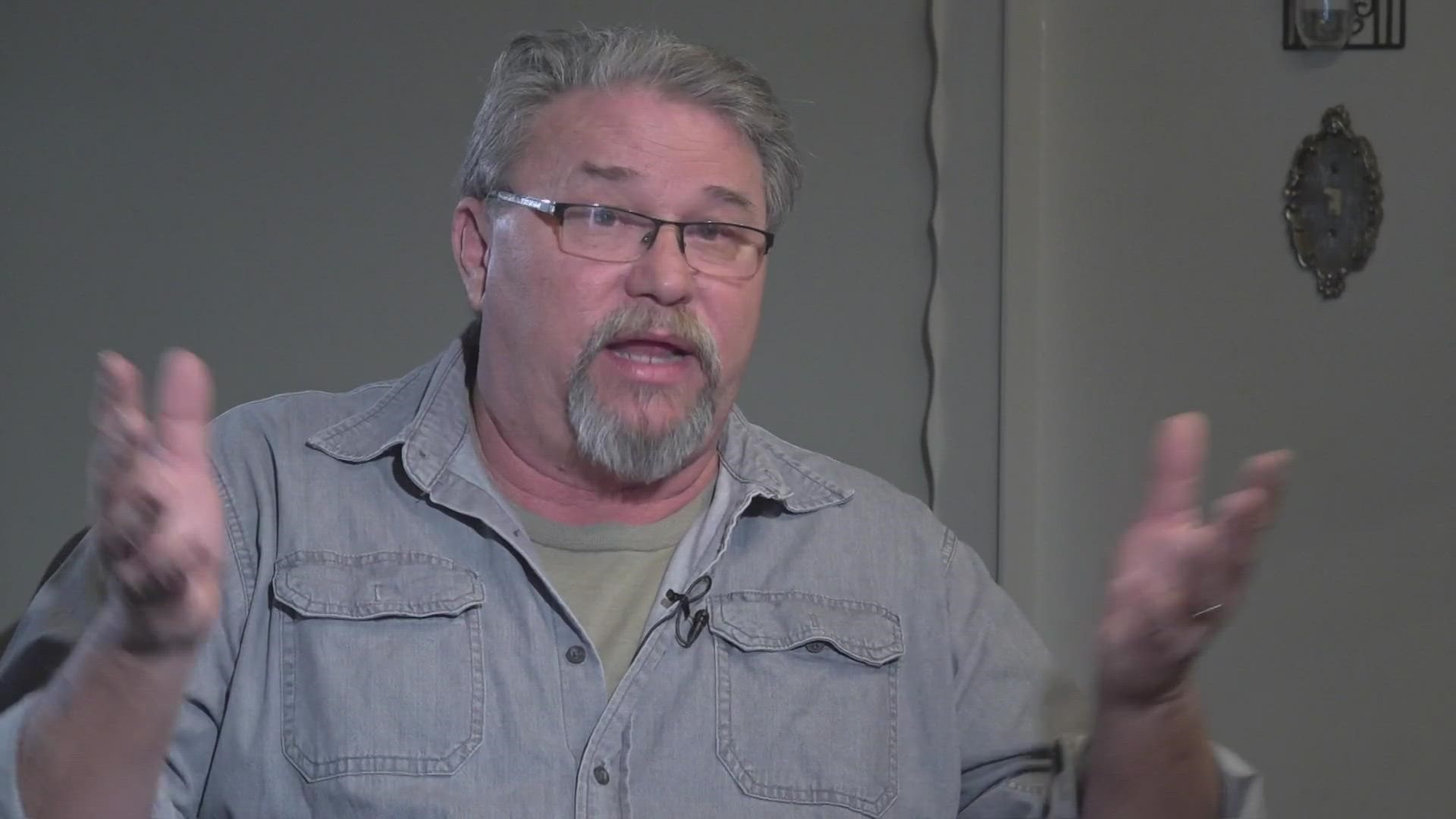

ST. LOUIS — Roger Murphey remembers how he found out he had been banned from St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner’s Office.

It was June 18, 2019. An email from then Maj. Michael Sack arrived in his inbox. The word “Notification,” was in the subject line.

It read: “The Police Division has been notified that Ms. Kimberly Gardner, the Circuit Attorney for the City of St. Louis, has placed you on the exclusion list, which prohibits you from presenting cases to the Circuit Attorney's Office. It was communicated to me that ‘This decision was made (by the CAO) after careful examination of the underlying bias contained in those social media posts (identified in the Plain View Project) that would likely influence an officer's ability to perform his or her duties in an unbiased manner.’ Therefore, effective immediately you are banned from the Circuit Attorney's Warrant Office pending an internal review. Until the review is complete, you are not to present yourself or cases to the Circuit Attorney's Office. Any cases you may have under review, in which you are an essential witness, will be refused. Search warrants in which you are involved will not be signed or approved.”

Murphey said he made the social media posts in question two years before the nonprofit Plain View Project flagged them as offensive. At the time he was one of about 20 St. Louis police officers added to the exclusion list. Gardner initially formed the list in the fall of 2018 with about 30 officers saying she found them to be untrustworthy.

But she keeps the identities of those officers, what they did to prove themselves untrustworthy, or how some of them regained that trust to get removed from the list remains shrouded in secrecy. Prosecutors elsewhere in the country make lists of questionable officers public, along with the reasons they are not credible and a process for officers to defend themselves.

Gardner refused our request for an interview, and issued a statement.

It read in part: “Unfortunately, there are officers whose past behavior has proven them to be untrustworthy in criminal proceedings that take away a person’s liberty. In order to preserve the integrity of the criminal justice system, we must consider credible sources of evidence.”

“It stopped me from doing the job,” Murphey said. “I couldn't go down to the office and file warrants. I couldn't apply on arrest warrants, couldn't apply on search warrants for phones, for records, search warrants for homes. It also affected me, as in testifying in open court.”

The St. Louis Police Department didn’t respond to the I-Team’s inquiries about the list.

The St. Louis Police Officers’ Association estimates there are now about 40 officers on the list. Union leaders only know when an officer tells them they’re on it.

Murphey thinks there are more.

In an email from then Chief John Hayden, Murphey was told: “As a reminder, department employees should not release the exclusionary list or any documents or information relating to the exclusionary list such as e-mails, inter and intra-department memos, and any other similar records. This list is a closed record under the Missouri Sunshine Law and should not be disclosed to anyone outside this Department. Anyone in violation of the above may be subject to discipline.”

“We can't talk,” Murphey said. “The guys won’t talk about it for fear of retribution from the department.”

The two Facebook posts that landed Murphey on the list include a screenshot of protesters blocking an intersection in downtown St. Louis following the acquittal of former St. Louis police officer Jason Stockley. He was a white police officer accused of murdering a Black man following a pursuit.

On Sept. 15, 2017, Murphey wrote: “So they’re protesting for a violent thug by breaking the law and Lying Lyda and kimmy g are backing them.”

Then, on Sept. 19, 2017, Murphey posted a link to a story about a man named Ashad Russell. It shows a screenshot of Russell walking toward a truck with a gun in his hand and is from the Missouri Firearms Coalition. The link includes text, which reads: “Stand-Your-Ground law for the win! This armed citizen strolls up, shoots this thug three times, saves a deputy’s life and calmly waits for the police! Thankfully Missouri has Stand-Your-Ground law on the books too, due to the members of the Missouri Firearms Coalition.”

Two years later, Murphey was added to the exclusion list.

At that point, he had been a homicide detective for seven years.

He said that assignment was his dream job.

“When you make it to the homicide unit, that’s the best-of-the-best right there,” he said.

Being added to the exclusion list shattered that for Murphey, who admits he grew bitter.

“They said I had a bad attitude,” he said. “If somebody wasn't asking me to do something, I just sat there and I’d watch TV, because I can't read another detective's cases. And they're not going to want their case screwed up because I've touched it because they put me on this list.”

Two months after he was added to the list, Murphey was transferred back to patrol.

He retired in 2021. It was four years earlier than he wanted to, and not the way he wanted to end a 26-year career.

“It hurt me,” he said, choking back tears. “And finally, I got to a point where I said, ‘I just I can't do my job anymore.’ And it's just like, ‘I'm not going to sit here and do nothing.’ So I just left, for my own sanity.”

Murphey contacted 5 On Your Side after the I-Team reported Gardner’s office has a backlog of about 4,000 cases that her prosecutors have not reviewed.

Seven of them are Murphey’s.

The exclusion list affected his other cases, too.

In 2018, Larry Keck was found beaten to death in his home on the city’s south side. He was 68 years old. Murphey was the lead detective.

He found evidence linking Keck’s ex-boyfriend to the crime. Gardner’s office issued murder charges. The case went to trial after Murphey was added to the list.

“I refused to testify for her office,” Murphey said, adding that defense attorneys tried to question him about the exclusion list during depositions. “You don’t get to call me names and impugn my character and then expect me to testify for your office.”

Nancy Koballa remembers how much Murphey’s absence at her brother’s trial was noticed. Prosecutors had to rely on the testimony of Murphey’s fellow detective.

“I'd say it was brought up probably 6 to 10 times during the trial,” Koballa recalled. “They questioned her numerous times as to why the original detective was not there.

“I had no idea why he wasn't there.”

The trial ended in an acquittal.

Koballa believes Murphey’s testimony could have helped.

“I would hope that it would have only because they questioned the validity so much, which made me think his testimony was crucial to this case, or they wouldn't have brought it up so much,” she said.

Koballa learned Murphey was on the list from the I-Team this week.

“I understand the reasons why he wouldn't have testified,” she said. “If he would have taken the stand, it would have become all about him and why he was on the list rather than my brother.”

Koballa said the exclusion list should be public, along with the reasons why officers get on it.

“If I would have known going into this that he wasn't going to testify and it would have been a huge issue, then I would have questioned, ‘Maybe we could have delayed the trial. Maybe we could have done something else,’” she said. “But we were not given that information, so nobody really told us the facts of why he wasn't there to testify.”

Most prosecutors use what’s called Brady lists to banish officers from pursuing cases.

They’re named after the court case that established them.

They’re public, as are the reasons why officers are on them. And they are most often used in court so defense attorneys know whether there are questions about an officer’s credibility.

In previous statements about the list, Gardner’s office has referred to it as a Brady list.

Chief Robert Tracy sees them as two different things.

“There’s two things, you talk about a Brady list, and then we talk about something that's called an exclusionary list,” he said “I've been meeting with some of our top command staff who have actually reviewed that with (the Circuit Attorney’s Office) and continue to review to see exactly where we're seeing some things that might be different from the Brady List.

“And I'm sure that's going to be a future conversation I'll have, but it's certainly something that I am looking at.”

Police union leaders say they support the use of a Brady list, too.

So does Murphey.

“I did nothing wrong,” he said. “I did nothing illegal.”

Still, he says, he thinks about the families like the Koballas that he couldn’t help.

“Every day,” he said. “Every day.”