ST. LOUIS — Caring for an aging loved one sometimes means making difficult decisions. When a family worries that a senior may be in danger the longer they live independently, nursing homes are supposed to be the safer option.

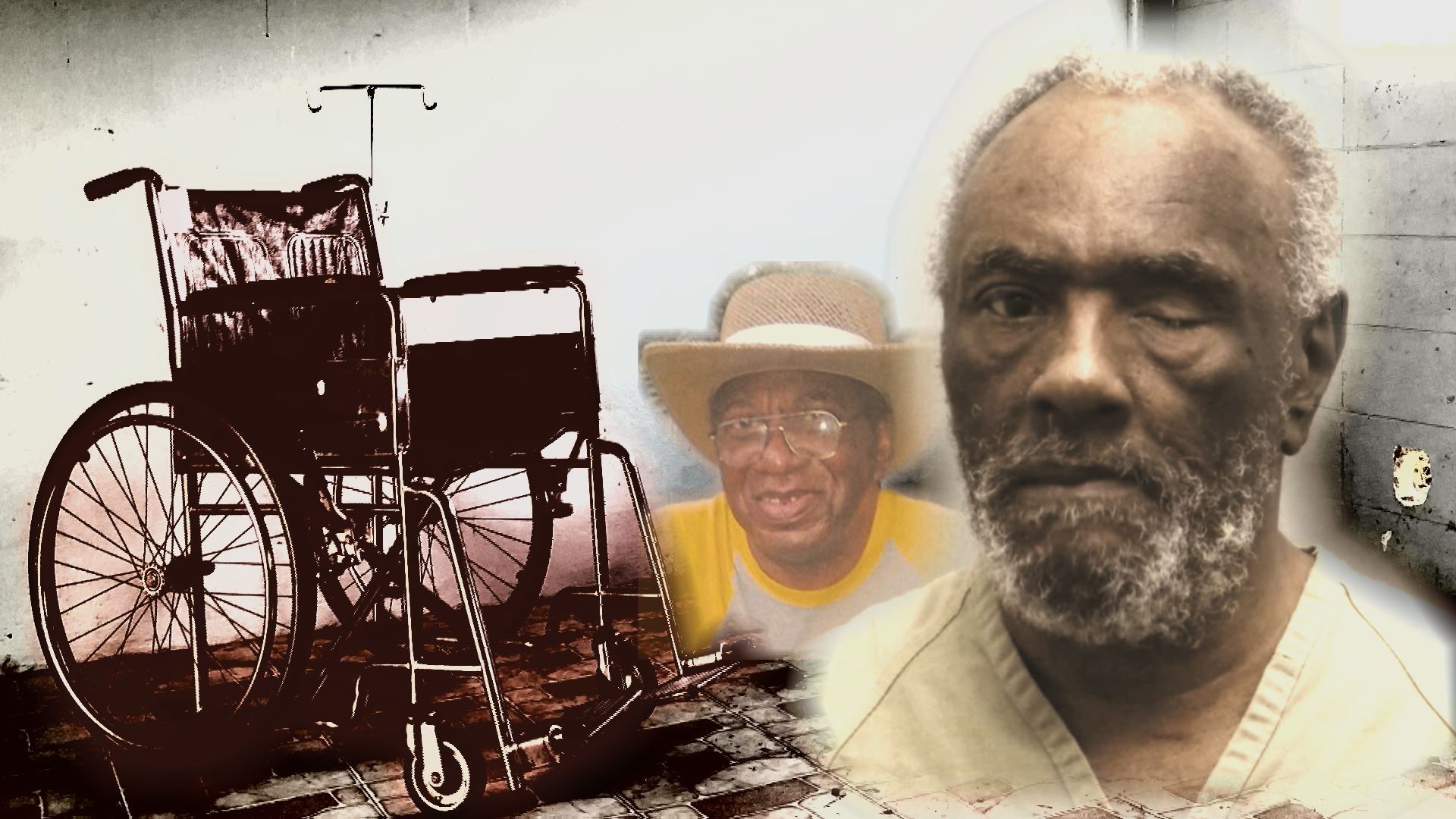

That’s why Christina Turner of Spanish Lake decided her father needed some extra care. Larry Harris was a retired postal worker and a proud grandfather of four grandchildren. Turner tried to care for him in her home, but at 64 years old, Harris was having problems with his memory.

“Sometimes he’d forget things and so I didn't want him to go out there and open the door and realize that he doesn't remember where to come back home to,” Turner said. “I was working, I couldn't have him in the house by himself.”

Turner chose a facility that offered round-the-clock care and was close enough that she could still visit him. She wanted to keep taking him to the parks and holiday events they both enjoyed. The Estates of Spanish Lake had all that and a secured unit to help Harris with his dementia diagnosis.

Putting Harris in a facility was supposed to keep him safe from himself. Dementia is a disease that affects every part of a person’s life. The declines that it causes in a person’s memory, mood, and coordination require full-time care. Turner had no idea that putting her father in a nursing home would expose him to a new danger that would take his life.

Harris seemed happy and healthy for five years. A report from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) said he was doing so well that the facility started helping him transition out of the secured unit to a new room on an unsecured floor, with the added precaution of a device to keep him from leaving the facility without permission.

The CMS report says Harris got a new roommate when he moved to the unsecured unit. The report calls him Resident No. 9. Police know him as convicted murderer Willie Clemons.

Resident No. 9

In January, Turner learned a lot more about her father’s roommate under the worst possible circumstances.

“They called me and told me that he had a heart attack, and then once I got there detectives told me that it was a homicide,” remembered Turner. A detective told her that Harris’s roommate was in custody.

“I never knew that he was a murderer until afterwards,” she added.

The staff at the Estates of Spanish Lake knew about Clemons’s criminal history because they did a mandatory screening when they admitted him to the facility in 2016.

That murder conviction is most likely the one resulting from the 1968 death of Phillip Christopher in Chicago. A document from the First District of the Appellate Court of Illinois says that a witness described the incident as a robbery gone wrong: “They were in the vicinity of Springfield and Roosevelt Road. They saw a man who appeared to be drunk…When the deceased came by the alley, the defendant grabbed him around the neck. The witness and another fellow went through the victim's pockets and took a small amount of money. Gary said he saw the defendant stab the deceased with a knife and then throw the body into a basement.”

Clemons, whose name is spelled Clemens throughout the criminal case in Chicago, served 17 years in the Dixon Correctional Center and was released in 1987. Illinois Department of Corrections staff confirmed that other biographical details between Clemons and the man convicted of killing Christopher in Chicago are identical.

When an inspector working for CMS interviewed staff after Harris died, they described Resident No. 9 as quiet but with a “mean streak.” Although the Estates of Spanish Lake initially admitted him to the secured unit, in 2017 he was in a room on the unsecured floor without a roommate. The report indicates that staff placed Harris in the room with Clemons “based upon the vacancy of a bed in his/her room on the unsecured second floor unit A, as well as them being close in age and having similar functional abilities,” the inspector wrote, adding “the two of them appeared to be pretty well matched. They were both pretty quiet.”

The inspector wrote that they interviewed Resident No. 9’s psychiatrist, who raised numerous issues with how the facility handled his patient’s care. The inspector found that the psychiatrist was last able to visit his patient five months before Harris died. In the two years that Resident No. 9 lived at the Estates of Spanish Lake, records showed that someone discontinued almost all of his mental health medications. The psychiatrist told the inspector that no one consulted them about the medication changes and the decision to move him from the secured unit to an unsecured room.

A nurse told the CMS inspector that in October, Resident No. 9 started reporting hallucinations that someone was spitting on him through the wall. The inspector wrote that the psychiatrist also had not been informed about the hallucinations.

Just after 7 a.m. on Jan. 2, hospital emergency medical services were dispatched to the Estates of Spanish Lake for a patient in cardiac arrest. The CMS inspector report says “Paramedics arrived on the scene at 7:14 a.m. and found the resident lying supine in his/her bed. The resident was bleeding and showed signs of what appeared to be trauma to the right eye and nose.” They were unable to resuscitate the victim.

The police narrative on the probable cause statement picks up from there, saying that Willie Clemons admitted to nursing staff that he punched the victim. The document says, “The defendant had apparent blood on his hands when he was arrested.”

Christina Turner was frustrated with the information she was able to get from detectives and the nursing home after her father died. She hired an attorney, Jermaine Wooten, to file a wrongful death lawsuit against the Estates of Spanish Lake.

They argue in their petition that Clemons should not have been anyone’s roommate.

“Given his mental state, given his aggressive behavior, he should have been inside of a secure area in this nursing home,” said Wooten. “This was absolutely ripe to happen.”

A violent year for Missouri nursing homes

The CMS investigator determined that the Estates of Spanish Lake didn’t meet requirements for mental and psychosocial concerns because it “failed to ensure two residents with mental disorders received treatment and services to meet their needs.” Using that report, the I-Team uncovered two other assaults connected to similar failures in Missouri nursing homes just this year.

A CMS report for Bridgewood Health Care Center in Kansas City states that a “physical altercation” on March 15 gave a resident a head injury so severe that they died of their injuries. Both residents, living in the dementia unit, had a history of aggression and attacking residents and staff.

Kansas City police confirmed that on that date, they responded to the nursing home for a report of an assault, but they didn’t know until contacted by 5 On Your Side that the victim had died. The KCPD Homicide Unit is starting a death investigation based on new information they received from the Jackson County Medical Examiner. They said that the victim was 60-year-old Elvin Coffman.

The CMS inspector stated in their report that the facility “failed to ensure residents with mental health disorders received appropriate person-centered and individualized treatment to meet the needs” of the involved residents.

A month before, a similar incident in Moberly at North Village Park left a resident using a ventilator and feeding tube due to trauma to their brain. The attacker, as identified by the CMS inspector, had been in prison for more than 20 years for a 2nd-degree murder conviction. After an aggressive outburst, the inspector wrote, they were placed in a room with the person who would end up being their victim. The roommates got in a fight over stolen clothes on Feb. 2.

Moberly police identified the victim as a 79-year-old man and said that the case is still active. The CMS inspector wrote that North Village Park “failed to ensure residents with mental health disorders received appropriate person-centered and individualized treatment to meet their needs” and “failed to adequately assess the residents’ specific needs and develop resident specific interventions as appropriate to address those needs.”

5 On Your Side reached out to Bridgewood and North Village Park for comment. The Department of Health and Senior Services also did not reply to questions sent in advance of publication.

No right to know

Elder law expert Christine Alsop told 5 On Your Side that the federal government requires nursing homes put together a plan of care for any type of resident they accept, even residents who come in with a history of violence or mental illness. The assaults in Missouri have many things in common, including the fact that documenting and responding to residents’ conditions didn’t go according to that plan.

Federal and state law includes no requirement to notify family of nursing home residents about who their loved ones are living with and whether they have a violent past. Details like that are protected under patient privacy laws.

“You're not going to get any kind of background information on a person who was living in a 15 by 13 room with your loved one,” said Wooten.

That means that families have little opportunity to ask for their relative to be moved away from someone who poses a threat until there’s already been an incident. Nursing home policies often specify that a resident’s guardian must be notified in the event of an aggressive or violent incident.

Turner said that if she knew who her father’s roommate was, she would have asked for a change.

“I don't think they should've been in the same room with each other. I think they should've had [Clemons] in a room by himself,” she said.

Finding out that vital detail after her father died was much too late to ask for change. Now, Turner is coming up on her first holiday season without her father.

“What I'm going to miss most is having him around on the holidays,” she said. “He was my heart.”

What you can do

Christine Alsop, who owns The Elder & Disability Advocacy Firm, recommends that families start discussing their care plans well before it becomes necessary to put someone in a nursing home.

“A lot of times I see clients who have waited until the end and they're now in crisis and they've been putting off the inevitable,” she said.

In Alsop’s experience, she said, nursing homes will tell families about the general characteristics and needs of their loved one’s roommate to ensure that they will get along. For more specific details about the roommate’s criminal history or diagnosis, the family can’t do much more than trust that the nursing home is managing the other resident according to their care plan: “A good nursing home is going to make sure that there's a separation between the personalities. They're going to know what personality is going to mesh with what personality.”

Alsop recommends that families visit nursing facilities unannounced to make sure they’re seeing the real conditions of residents’ care and, if possible, to talk to both residents and other visiting families. She said that any family member with concerns should be vocal about what they want changed and be willing to call police if they feel there is criminal activity happening.

There is also an ombudsman program run through the advocacy organization VOYCE where anyone can call an expert with questions about long-term care.

In Missouri, inspection records for nursing homes are available on the Show Me Long Term Care website from the Department of Health and Senior Services. The site that displays these records in Illinois is run by the state’s Department of Public Health.

Most states have a website of their own, and all Medicare- and Medicaid-certified facilities can be viewed on the CMS Nursing Home Compare page.

MORE INVESTIGATIONS

- Metro East 'vanishing mechanic' charged with deceptive practices, turns self in

- ‘Unfortunately nothing we can do’ | Florissant police accused of not doing enough in investigating child abuse

- Artist sketches portrait of what Angie Housman would look like today for her father

- Woman says forgotten classmate has stalked her for 9 years since high school reunion

- Escaped wallaby leads investigators to controversial Franklin County 'pet ranch'